Things the natural world shows us about designing for collective use and re-use.

Ground moss has been on my mind. It grows in cracks and corners no one planned for, spreading quietly until it is everywhere. It softens what weather and time have worn down. It holds water, sustains ecosystems, and persists without spectacle.

This is not a study of bryophyta sensu stricto in applied design, but a way of noticing how it works. Moss reminds me that design, like nature, can embody resilience without excess. Its usefulness and sturdiness mirror the best of a well-wrought concept or object: balanced, durable, and clear in purpose. Good design respects scale and proportion, sets a hierarchy of needs, and invites participation through obvious affordances. Affordances are the built-in cues that make use clear, like a handle that asks to be pulled or a slot that shows where something belongs. Like moss, good affordances settle into the gaps of fast systems and make use of what is here. They connect people through shared use and meaning.

From moss, a few practical principles:

- Fit the place. It takes to the surface it finds. Design for context and retrofit, not blank slates.

- Use little. It thrives on low inputs. Favor low-resource materials and simple maintenance.

- Hold and release. It stores water and buffers extremes. Design to buffer loads, temperature, and wear over time.

- Make habitat. It creates microclimates for other life. Shape spaces that support people and shared use, not just objects.

And perhaps that is what makes it a fitting teacher: moss persists by adapting to available conditions. Design can do the same, taking root and thriving in overlooked spaces.

Tangent I: Designing for the Whole

There’s a gentle swell toward collective approaches. Have you noticed it?

Design philosopher Tony Fry writes that modern design too often “defutures” the world. It solves short-term problems while generating long-term ones, with fast fashion, fast food, fast everything. It is not only resource-extractive; too often, it is also meaning-extractive. Meaning is stripped when objects are made disposable, when cultural memory is flattened into trend, and when use is severed from care. There is a longing for a more communal way of living, one that values participation, connection over consumption. You can see it in the rise of mutual aid networks, co-housing projects and community gardens.

Some places make this tangible. In Kamikatsu, Japan, neighbors sort discards into dozens of categories and turn waste into inputs. It required daily inconvenience, shared standards, and clear feedback. The system works because it uses hierarchy, labeling, and visible affordances that make the correct action easy. This is what good design can do. It makes participation practical and repeatable. Here, moss returns to mind: thriving because each fragment of the system plays a role, no matter how small. Like moss, the collective thrives not because of one strong element but because of many small acts that hold together. The return to well-made vintage goods follows the same logic: every time we choose repair over replacement, or re-use over disposal, we are practicing design for the whole.

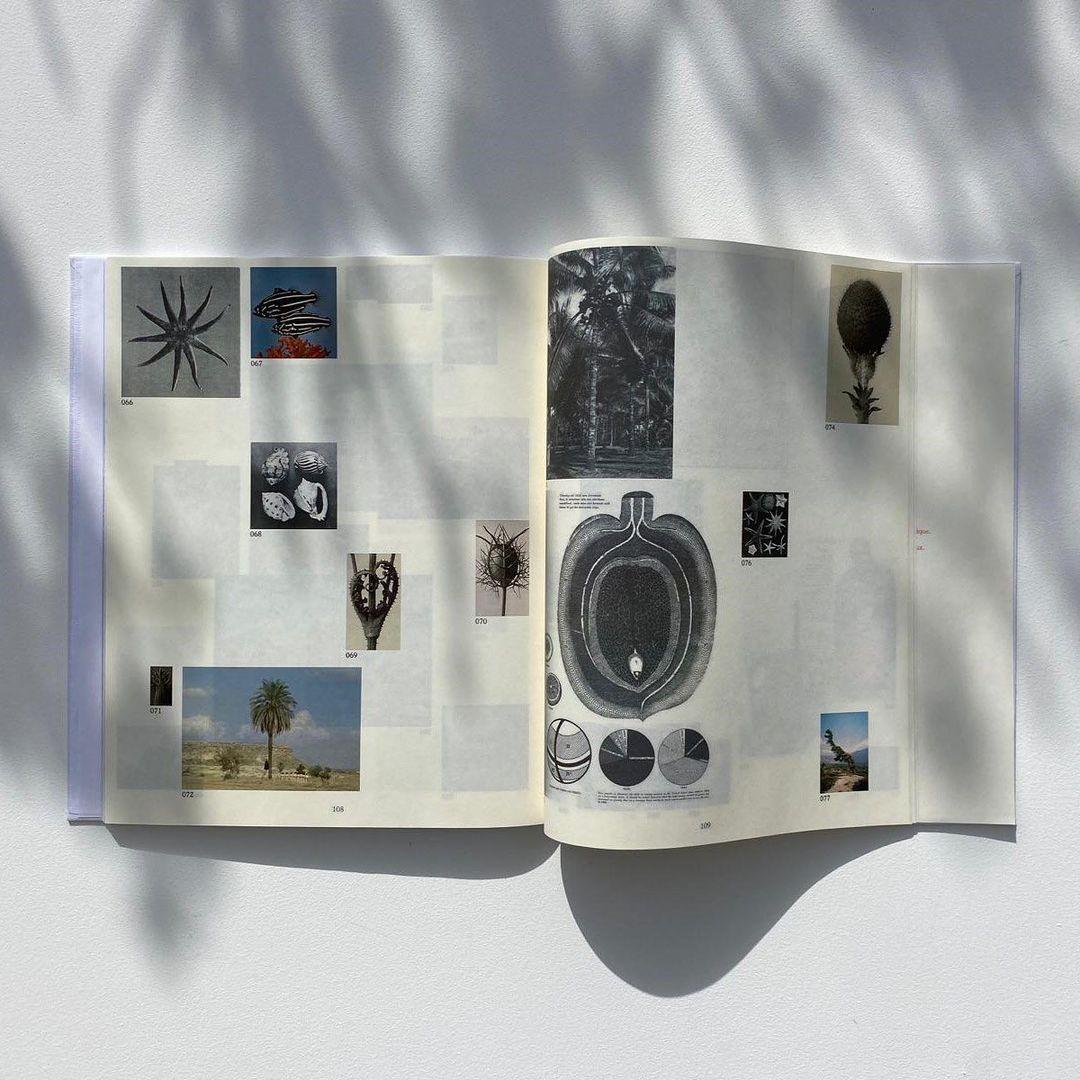

Tangent II: What Nature Knows

Nature never wastes. It rearranges. A fallen leaf becomes soil.

Termite mounds use air pressure and section geometry to cool interiors, and architects have applied this to reduce mechanical conditioning. The lesson is simple: form should serve function, and cycles of use should be built into design. This is biomimicry at its most practical: borrowing principles from nature to design systems that sustain themselves. A well-made piece follows the same path. It stays adaptable and repairable, respects constraints, and remains legible without instruction. Its value increases with time because it is used, maintained, and kept in the loop rather than discarded. Nature reminds us that continuity is never solitary, cycles endure because each part contributes to the larger system.

Tangent III: The Quiet Return to Wholeness

Design, at its most nourishing, is a communal act. I am still learning how to see this way and how to live this way. It does not come naturally all the time, especially in a world that tells us to move faster, to produce more, to stay ahead. I forget that slow is still allowed. And then I notice moss holding to the side of an old wall, or a chair whose wood has been polished smooth by decades of passing palms. I see a building that breathes with the land instead of against it. And I remember. Small is not lesser. Gentle is not fragile. And slow, slow processes do not have to mean idle. Slow can be a practice of fortitude that values depth of use over breadth of output. Sometimes, it simply means choosing the unhurried path, the one that listens before it builds, that lingers long enough for roots to knit quietly beneath the surface. Slowness also allows for shared processes such as repair, re-use, and memory, all of which require time to accumulate.

Good design, then, is not defined by novelty. It is measured by how well it serves over time, how lightly it treads on resources, how openly it invites participation, and how deeply it sustains connection. It is durable, adaptable, and repairable. It respects the past, makes sense in the present, and leaves room for the future. Like moss, it takes little but gives much. Even quietly. Maybe most of all that way.